MASS IN C MINOR

INTRODUCTION

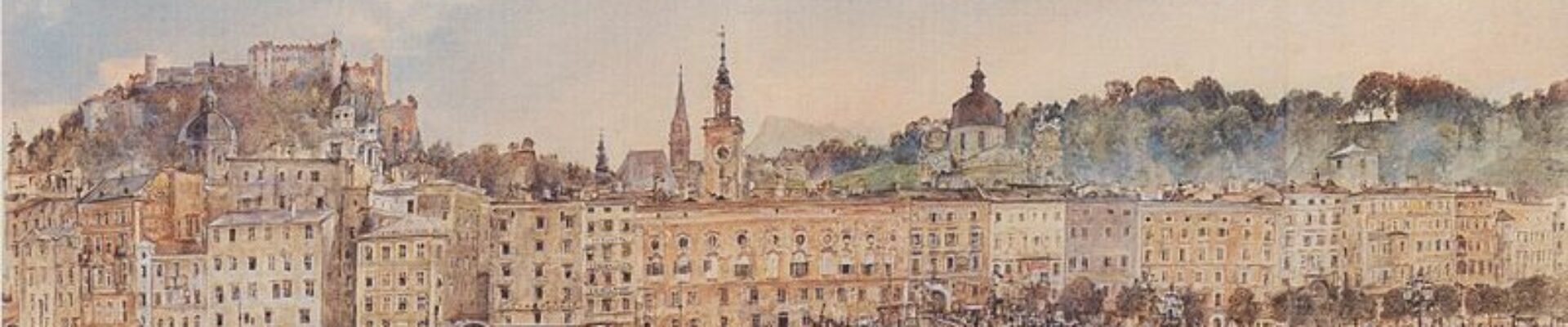

This is Wolfgang Mozart’s first mass, written in Vienna, predating “K49” by a month or two in the fall of 1768. It was long thought that no twelve year old, even if his name was Mozart, was capable of the sophistication of this work—hence the Köchel1 number suggesting composition several years later. However, there is now no doubt that this is the mass performed at the dedication of the new church at the Orphanage on the Rennweg (that’s a street) in Vienna, commissioned by its director, Jesuit priest Father Ignaz Parhamer.

The Jesuits at mid-century were generally in the favor of the Habsburg Imperial court due to their ministry to the poor and to children, which was strongly in concert with Enlightenment principles. Father Parhamer had led missions to many places, including Salzburg ten years earlier in 1758. His widely used catechism was designed to combat ignorance, which he believed to be the origin of all sin, and to instill the love of God and the commitment to a moral life. He assigned a lay supervisor to groups of ten: small children, older boys and girls, artisan apprentices, and male and female servants. He then formed “confraternities” in the community, voluntary groups of citizens who pledged to live moral and upstanding lives as models for his scruffy souls.

At the end of the catechism instruction, the groups from around the countryside would march behind flags of their own devising to a central location, accompanied by military trumpet music. There they would publicly renounce the Devil and all his works and pledge themselves to God, followed by the singing of a grand “Te Deum”. Archbishop Sigismund von Schrattenbach, pious and ingenuous, was a sucker for pomp and ceremony. He was so impressed that he himself joined the Salzburg confraternity, as did most of his own court, including Leopold Mozart (Wolfgang was only two years old in 1758, but he joined later as well).

There was thus a useful history for Leopold in Vienna with Father Parhamer. A first performance of Wolfgang’s opera “La Finta Semplice” had been scuttled due to Leopold’s unsuccessful political intrigues, but Father Parhamer was also now an Imperial court insider due to his having been confessor to now Dowager Empress Maria Theresa’s late husband Emperor Francis I and was able to offer the commission for a mass instead. The Empress herself even came to the orphanage to hear the performance.

STRUCTURE

“K139” is a carefully divided cantata mass, with the Kyrie split into three separate sections, the Gloria into seven, and the Credo into seven. Mozart does not subdivide “Domine Deus”, “Qui tollis”, or “Agnus Dei”, as earlier composers often did. He does retain their other common practice of setting “Dona nobis pacem” as its own movement separate from the other words of “Agnus Dei”. These specific choices are close to those in Leopold’s “Missa Solemnis”, which Wolfgang must have had next to him on the composing table, aided by Leopold’s guiding hand.

TIC = Type I Chorus; TIIC = Type II Chorus; S,A,T,B = Solo Soprano, Alto, Tenor, Bass

Kyrie

Movement/Section

“Kyrie eleison” Intro

“Kyrie eleison” I

“Christe eleison”

“Kyrie eleison” 2

Leopold, “Missa Solemnis”

(“Kyrie” I acts as Intro)

Slow —TIIC, cries to heaven

Fast—“Kyrie” mixed in

Fast—“Christe” mixed in

Wolfgang, “K139”

Slow—TIC, cries to heaven

Fast—“Christe” mixed in

Slow— All “Christe”

Fast—“Christe” mixed in

Gloria

Movement/Section

“Sanctus”

“Pleni sunt caeli”

“Hosanna in excelsis”

Leopold, “Missa Solemnis”

TIC

TIC

TIC

Wolfgang, “K139”

TIC

TI/IIC

TIIC

Credo

Movement/Section

“Sanctus”

“Pleni sunt caeli”

“Hosanna in excelsis”

Leopold, “Missa Solemnis”

TIC

TIC

TIC

Wolfgang, “K139”

TIC

TI/IIC

TIIC

Sanctus

Movement/Section

“Sanctus”

“Pleni sunt caeli”

“Hosanna in excelsis”

Leopold, “Missa Solemnis”

TIC

TIC

TIC

Wolfgang, “K139”

TIC

TI/IIC

TIIC

Benedictus

Movement/Section

“Sanctus”

“Pleni sunt caeli”

“Hosanna in excelsis”

Leopold, “Missa Solemnis”

TIC

TIC

TIC

Wolfgang, “K139”

TIC

TI/IIC

TIIC

Agnus Dei

Movement/Section

“Sanctus”

“Pleni sunt caeli”

“Hosanna in excelsis”

Leopold, “Missa Solemnis”

TIC

TIC

TIC

Wolfgang, “K139”

TIC

TI/IIC

TIIC

Leopold’s “Missa Solemnis” is scored for obbligato flute, 2 trumpets, 2 horns, timpani, violins, violas, basses, and organ continuo.

Wolfgang’s “K139” is scored for 2 oboes, 4 trumpets, 3 trombones, timpani, violins, violas, basses, and organ continuo.

SOUND

But beyond the structure of the movements, the “sound” of Wolfgang’s music, even in this formal showpiece introducing the young genius to Vienna’s religious cognoscenti, shows a playfulness and ingenuousness all his own. By now he had tried his hand at sonatas, concertos, symphonies, and operas—sophisticated music addressed to the sophisticated audiences of royalty and nobility who might offer a commission or would at least pay to get into a subscription concert.

Church music had a different audience: as we have seen (“Cantata Mass Trends, Vienna”), the Habsburg royalty had little interest in paying for Catholic music, and back in Salzburg church music would be a routine expectation of menial employment at the archbishop’s court. The nobility had their private box seats in church, but the celebration of mass was for the saving of peasant souls as well—and admission to mass was free.

I think there is evidence in the music itself that Mozart, perhaps with Father Parhamer’s inspiration, directed his masses at farmers, laborers, peasants, shop clerks, and children, including the child in all eager, uninitiated listeners—like us. This audience would have whistled folk tunes at work, bellowed drinking songs in pubs, danced the Ländler in barns, sung lullabies to their children at home, and gone to mass on Sundays. The growing trend in lyrical, accessible folklike music that we have noted in the cantata masses of southern Germany would have attracted this population perfectly.

A NOTE ON MUSICAL EXAMPLES

There are four recordings of the complete Mozart masses, and I would recommend that the serious listener purchase one.

My personal favorite is the Philips set that features conductors Uwe Christian Harrer, Colin Davis, John Eliot Gardner, and mostly Herbert Kegel (13 of the 16 Salzburg masses). I like the set because of the way Kegel handles the three groups of chorus, soloists, and orchestra. You always hear each group clearly, even when it is in the background. Even more remarkably, you hear each soloist individually in a duet, trio, or quartet while the voices still blend beautifully. Unfortunately, most of the soloists, especially the sopranos and tenors, are warbly and “operatic,” not as pleasing to the ear for my many brief musical snippets.

On Teldec, Nikolaus Harnoncourt’s approach is so homogenous that the orchestra, chorus, and soloists sound as if they have been put through a blender such that nothing stands out from anything else, although he has better soloists.

The set I have used for musical examples by default in these essays is the one conducted by Nicol Matt on Brilliant Classics. His approach is balanced, the chorus and soloists are more than adequate, and the price is great.

Where I have a point to make about tempo or interpretation, I will bring in one of the other versions for comparison.

After the first drafts of the chapters for all the masses were written I found a fourth complete set by Peter Neumann on EMI briefly for sale in 2018, but it is no longer available. He has excellent soloists. His sound is on the smooth side, like Harnoncourt, but with Kegel’s excellent demarcation of chorus and soloists. The orchestra is generally in the background and lacks Kegel’s exuberance.

KYRIE

KYRIE 1

The first “Kyrie” section opens solemnly and slowly in the minor mode with a Type I chorus. There is no tune, just a series of cries to the heavens. Suddenly the major mode breaks forth and remains the predominant sound for most of the rest of the mass. It is as if Mozart has made a conscious decision at this point to abandon doom and gloom and to concentrate on “making a joyful noise”. There are a couple of lines for soloists but this is really a showcase for chorus. The sound is merry and infectious and it is hard to tell if the orchestra or the chorus are having more fun. There is such a liberal admixture of the phrase “Christe eleison” that when the four minutes of music comes to a satisfying conclusion, it would be easy to infer that Mozart is now done with the entire Kyrie movement.

CHRISTE

However, an exquisite slow section for soloists follows with new thematic material, and all on the words “Christe eleison”. The music is tender and swaying and is constructed mostly in thirds and sixths, giving it the open and childlike sound of a song in two verses. The soprano, alto, and tenor take sequential entrances in the first verse. As the bass begins the second verse, there is a sudden magical chord progression to the minor mode which leads to a brief rhapsodic working out of themes to finish the verse.

KYRIE 2

The merry and infectious section repeats, “Christes” and all, ending the Kyrie on an upbeat note. In this first movement are tunes enough for half a mass, but Mozart will give us many more before he is done.

GLORIA

GLORIA IN EXCELSIS DEO

“Gloria in excelsis Deo” is a type I chorus. It leaves no doubt that the minor mode has been left far behind. The music is bright and jubilant.

LAUDAMUS TE

“Laudamus te” is an ingenuous song, as rediscovered, by Leopold in his “Missa Solemnis”. The alto and soprano each sing a verse and then finish as a duet in thirds and sixths. The music is soft and swaying like a lullaby.

GRATIAS AGIMUS

The chorus return in a brief and impassioned Type I “Gratias agimus”. The second line, “Propter magnam gloriam tuam”, is usually set as an integral part of “Gratias”. Here it is set separately and so awkwardly it sticks out like a sore hum. In about eighteen seconds of music, Mozart uses eight chord changes to get from D minor to A flat major and six more to get from A flat major to C minor. This is a similar to the technical problem which Leopold Mozart was trying to solve around the line “Filius Patris” in the Gloria of his “Missa solemnis”. Neither composer succeeds.

DOMINE DEUS

“Domine Deus” is a song for tenor and bass. It is difficult to create musical settings for the male solo voice which do not sound pompous or arrogant (remember Leopold’s tenor aria on “Et in unum Dominum” in the Credo of his mass? This is why the male solo voice is so well suited for opera. The female solo voice, of course, is equally capable of such bleating, but the soprano much more so than the alto. Most leading male roles in opera are tenors, to be sure, but there are many important bass roles as well. However, it is rare to find an alto singing a leading role in opera). In this song there is no self-importance, the two male voices combining in a lovely, tender ballad.

QUI TOLLIS

The music becomes very serious for “Qui tollis”, a somber entreaty for mercy. The chorus is Type I, the chords long and slow with all singers singing the same syllables at the same time. A sense of great tension and urgency, however, is created by the sophistication of what the orchestra is doing. While the chorus is singing one note for every beat or every two beats, the lower strings are playing two notes for every beat and the upper strings are playing three notes for every beat. The result is hard to play, hard to conduct, and hard to grasp with the ear, creating an unsettling effect.

QUONIAM

As quickly as they rolled in, the clouds depart for the bright and jaunty “Quoniam”, an ingenuous folk song with a sound which appeals directly to the child in every member of the congregation. It is often called by scholars “operatic” because of its melismatic runs, but this song is so buoyant and irrepressible, it puts me in mind of a girl dancing around the Maypole or stomping gleefully on the grape harvest singing “tra la la la la.”

Let me pause for a moment to rant about this. Soprano arias, whether from operas Mozart wrote in his teens, his twenties, or his thirties, are of a very different character than this song. His opera arias, whether “serious” or “humorous”, have a polished, self-absorbed tone designed to appeal to the sophisticated, important people of their audiences.

Here is, for example, an absolutely contemporaneous aria, “Colla boca”, from “La Finta Semplice”, Wolfgang’s opera which had just been unceremoniously cancelled. It is also bright and jaunty.

The coquette Rosina’s task is to soften the hearts of two rich Italian bachelor brothers to permit the marriage of a Hungarian army captain and his sergeant, billeted at the brothers’ house, to the brothers’ sister and the sister’s maid, respectively. Rosina makes both brothers fall in love with her by pretending to be a naïve simpleton, then helps the other characters pretend to steal the brothers’ fortune and then “find” it again. This does the trick, for some reason, and all ends well, with Rosina herself marrying one of the brothers, while the other ends up with no one. Ha ha. The royals and nobles just loved this stuff.

Rosina is telling us that causing someone to fall in love is done with the mouth, not with the heart, and that while you can please everyone, you can love only one. Rosina is most definitely not ingenuous. This is an “operatic” sound, with music which suits the words well—a sound completely different than our “Quoniam”.

The ingenuous songs of the masses are like lullabies or folk songs that speak directly to us children. The music may be innocent or saucy or irreverent, but is never disrespectful of the words it supports.

CUM SANCTO SPIRITU

A crisp, joyous Type II chorus on “Cum Sancto Spiritu” concludes the Gloria in grand fashion.

CREDO

CREDO IN UNUM DEUM

“Credo in unum Deum” opens just as grandly with a crisp, businesslike Type I chorus accompanied by an almost frenetic orchestra part. It sweeps us without a pause through the words “Descendit de caelis”. The music characteristically falls, following the meaning of the words, but takes its time getting Jesus to earth, as if He wafts for a bit, then stops to dance a couple of times along the way.

After an initial glorious Type I chorus, Leopold’s mass had set most of these first seventeen lines as an Italian-style tenor aria. Wolfgang here strikes out on his own, setting them in short chunks, using the rather simple organizing scheme (hey, the kid is twelve!) of ascending and descending pieces of the scale separated twice by a fragment alternating two notes. I say “simple”, but it doesn’t just sound like scales going up and down at all (although the frenetic orchestral motif does); rather more like one jaunty theme fragment after another. The section is too long to quote all of the examples here, but listen with the words and you will hear the chunks beginning:

“Credo in unum Deum”—descending X 2 (snippet above)

“Patrem omnipotentem”—descending (chromatic) X 3

“Et in unum Dominum”—alternating X 2

“Et ex Patre natum”—ascending X 4

“Genitum, non factum”—alternating X 2

“Consubstantialem Patri”—ascending X 2

“Per quem omnia facta sunt”—descending X 1

“Qui propter nos homines”—ascending X 2

Each scale fragment is four notes long until the last one, at “Descendit de caelis”, which appears to be six. But Mozart pauses, cocks his head, and repeats the phrase, inserting a rest after the fourth note, as if to say, “There: that’s four (with two left over)”.

ET INCARNATUS EST

“Et incarnatus est”, set for soprano and alto duet, is really another ingenuous song. With harmony set quietly in thirds and sixths, this might be a lullaby for the baby Jesus.

CRUCIFIXUS

The music turns suddenly to the minor for “Crucifixus”, a stern Type I chorus accompanied by three trombones, timpani, and muted trumpets. The rhythm is almost identical to the same section in Leopold’s mass and the presence of muted trumpets makes it clear that Leopold’s was a direct model (Wolfgang does not lift the tune of Eberlin’s “Mass No. 34”, which Leopold does).

ET RESURREXIT

The unaccompanied soprano begins the “Et resurrexit” to stunning effect, leaving no doubt in the congregation’s minds that Jesus lives. The chorus take over in spirited Type I fashion, with bits and pieces of the frenetic orchestra part from the opening “Credo”. The music ascends with the words “Et ascendit in caelum”, pausing dramatically and respectfully for “et mortuos”. In the setting of the line “Cujus regni non erit finis”, Mozart has the chorus repeat “Non” seven times in a row.

ET IN SPIRITUM SANCTUM

“Et in spiritum sanctum” is a lovely ingenuous song for solo tenor.

ET UNAM SANCTAM CATHOLICAM

The chorus return briskly for “Et unam sanctam catholicam”, again accompanied by the frenetic strings. Again the music pauses dramatically for “mortuorum”.

ET VITAM VENTURI SAECULI

The Credo closes with a Type II chorus on “Et vitam venturi saeculi”. The music is so jolly and exuberant, who could fail to be won over to belief in the “life of the world to come”? Mozart completes the playfulness by assigning to the final “Amen” the same music he had used for the repeated “Non” in “Non erit finis”, accompanied one last time by the frenetic string motif.

SANCTUS

“Sanctus” opens as a stately Type I chorus, which continues for the first statement of “Pleni sunt caeli”. The second and third statements become ever more imitative, until by the start of “Hosanna”, the music is all Type II.

BENEDICTUS

“Benedictus qui venit” is a lovely ingenuous song for soprano, again sung as a lullaby. Mozart anticipates the return of the imitative “Hosanna” by having the chorus answer each solo line with gentle cries of “Hosanna”.

AGNUS DEI

C minor returns one last time for the solemn “Agnus Dei”.

Despite having four trumpets and three trombones at his disposal, Mozart has so far resisted setting a solo voice against any of the brasses, perhaps recalling the near-disastrous coupling of bass voice and trumpet by Leopold in “Et unam sanctam catholicam” of his mass. Here Wolfgang begins the reverent “Agnus Dei” with the three trombones as an introduction and then adds the solo tenor to near-hypnotic effect. The blending of the four voices is perfect, and, wisely, he does not beat it to death. The second statement of “Agnus Dei” is by the full chorus, with the trombone part now assigned to the strings, which blend much better than brass instruments with the chorus. Finally, entering one voice at a time, the soloists take the final verse.

DONA NOBIS PACEM

The quiet mood is broken once more for a final joyous Type I Chorus in C major on “Dona nobis pacem”.

Leopold Mozart gave up composing sometime in the late 1760s. It is generally assumed that this was to allow him more time to promote his son’s career. In addition, I suspect he read over the final draft of “K139”, shook his head, and muttered to himself, “That’s it, I’m done”.

![]()