MASS IN C MAJOR, K167

INTRODUCTION

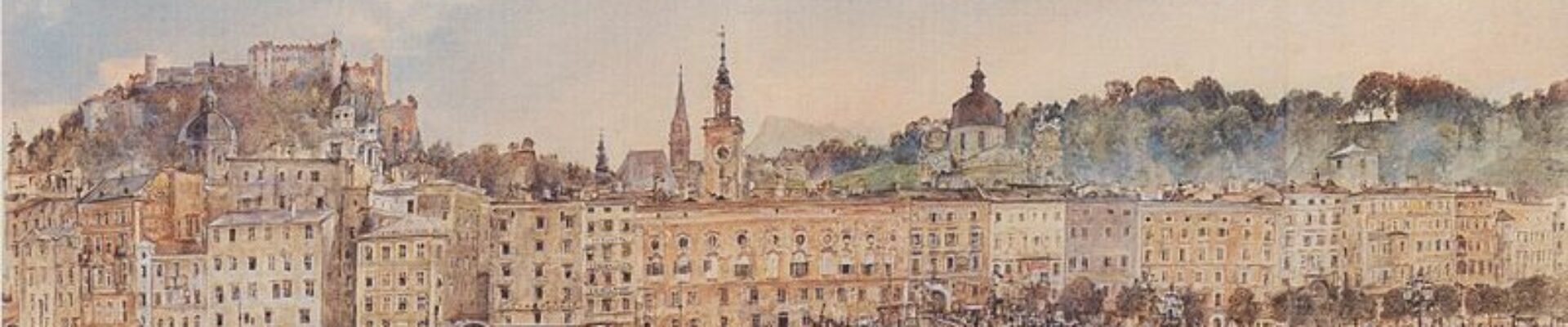

This mass was written in June, 1773, and Mozart himself titled it “Mass in Honor of the Most Holy Trinity”. As Trinity Sunday was on 6 June that year, it was most likely first performed on that date, though where is unknown. Different sources suggest the cathedral, the Benedictine Collegiate Church, and the Trinity Church, so take your pick.

Wherever it was performed, it is clear that the archbishop was watching, as there are no violas in “K167”. It is scored for 2 oboes, violins, bass, organ continuo, and three trombones doubling the alto, tenor, and bass singers. However, it also includes 4 trumpets and timpani, supposedly forbidden in the edicts of Rome and Vienna. It seems that “in the countryside”, away from the power centers, standards were pretty relaxed, as the archbishops and other nobles with their own orchestras liked pomp and flair and made many dispensations for these and other “festive” instruments. Colloredo was no exception.

But as we know, the archbishop also liked masses he celebrated to be short. He did not like the total length of the service to exceed forty-five minutes, including readings, chants, and other music. This meant the Kyrie, Gloria, Credo, Sanctus, Benedictus, and Agnus Dei had to be limited to about twenty minutes. “K140” lasts just over sixteen minutes—well and good. “K167” runs over twenty-nine minutes, which may at the very least mean that it was not sung at the cathedral. We may guess that the archbishop was not pleased and made his young employee well aware of it.

This is the only one of Mozart’s masses without vocal soloists, for reasons known only to him. Perhaps in compensation, the orchestra has a prominent role, with introductions and interludes in several movements. And as we shall see, Mozart has an obsession with musical scale runs here that may not have actually left him any room for soloists.

KYRIE

After a brief orchestral introduction, the chorus pick up the catchy Type I tune—call it ”Kyrie1”. It is in duple time, majestic and festive, inviting everyone to pull up a pew and listen to the music. The movement is conveniently divided into three sections of about a minute each—we would think, “Kyrie eleison”, “Christe eleison”, “Kyrie eleison”, right? Wrong again. After an orchestral interlude, the music turns suddenly to the minor key and a new theme appears—the perfect place to switch to new words. But “Kyrie eleison” continues—call it ”Kyrie2”. “Christe eleison” gets its own music, but it’s more a bridge than a section, a scant twenty seconds, before the return of the initial “Kyrie eleison” music—call it ”Kyrie3”—which finishes the movement.

In all of “Kyrie1”, aside from some supporting runs in the tenors and basses, Mozart never gives the tune more than three notes in a row of the scale, up or down. Then, at the dramatic shift in theme at “Kyrie2”, the sopranos sing a prominent, drawn-out five-note ascending scale motif, in which the voices enter in rapid succession. Just afterward, in “Christe”, following a loud outburst by all the singers, all the other voices sing quietly while the tenors continue loudly with their part, a prominent five-note descending motif. Finally, the tune for “Kyrie3” is altered to give the sopranos a four-note rising motif and two five-note descending motifs (#1, #2) that weren’t there before. They then finish the movement strongly on four descending notes, which are repeated. These phrases are of no particular moment structurally for this movement, but represent a kind of “throat-clearing” by Mozart for what is to come.

GLORIA

Gloria, all in triple time, begins as a Type I chorus on the words “Et in terra pax”. There is no formal division of sections, but a constant stream of new melodies gives several of Mozart’s characteristic text groupings their own distinct characters. “Laudamus te”, “Gratias agimus”, “Domine Deus”, and “Qui tollis” are handled in this fashion. The tune of the opening bars returns for “Quoniam” and the movement finishes with a rousing Type II chorus on “Cum sancto spiritu”.

But there is more here in the way that Mozart binds together the text. He weaves a common thread through the series of brief merry tunes and bits of text by means of a short recurring figure. It is not a tune in itself, but contains both rhythmic and melodic elements. The device is basically four accented notes going UP THE SCALE in some places and down in others. Sometimes it is major, sometimes minor. Sometimes the run is extended to five or more notes, but the prominent sound is four.

It is most obscure in “QUI TOLLIS”, where the violins play the first note and the chorus sing the next three, further disguised by a gap between two of the notes, but this is simply the proper spacing of the last four notes of the ascending minor scale.

There is almost no place until the final chorus where four or more notes in a scale do not occur together. Upper case means ascending, lower case means descending.

Glorificamus te.

Deus Pater omnipotens.

QUI TOLLIS PECCATA peccata mundi,

miserere nobis.

suscipe deprecati-onem nostram.

Qui sedes ad dexteram ad dexteram Patris,

MISERERE MISERERE miserere nobis.

Quoniam tu sol-US TU SOLUS SANCT-us,

TU SOLUS ALTISSI-mus,

Al-tissimus, Jesu Christe Jesu Jesu Christe.

Finally, the Type II chorus “Cum sancto spiritu” gets into the motif, but with a spirited twist. The orchestra think they are returning to the opening music of “Et in terra pax”, and play the distinctive rising motif, but quickly give it up. The first four syllables in each vocal group are strongly accented, but instead of ascending or descending the scale, it is the same note. This has the effect of “canceling out” the previous usages. The countermelody in each voice very carefully avoids more than three notes in the scale in a row, so the monotone appears to have the final say with the motif. But the sopranos apparently can’t stand it, and as they begin an extended “Amen”, they begin four- and five-note runs—I count four times up and three times down—with each of the other groups chiming in with a couple of their own, and just before the end, three more strong times down.

CREDO

At this point, any other composer would have exhausted the possibilities of playing with a fragment of the scale. Mozart, however, shifts into duple time, expands the default scale motif to five notes or more, and does something entirely different for the Credo, which is long and complicated.

The movement is organized into six sections: fast-slow-fast-slow-fast-fast, all permeated with ascending and descending scale runs. The fast sections are further unified by three brief distinctive theme fragments. The sequence of notes sung by the chorus is not the same in each fragment appearance—sometimes not even close—but the combination of rhythm, chord change, and orchestral accompaniment give each fragment its own easily recognizable sound. Each is present twice in the first fast section and once in the second. Two of three appear in the third fast section and the missing one fills out the fourth.

PATREM OMNIPOTENTEM

The key for the listener is found in the first thirty seconds of the first fast section, in which each of the three fragments is stated, one after another.

Fragment A begins with “PATREM OMNIPOTENTEM” and contains five ascending notes. It is quite similar to the theme of “Et in terra pax” from the Gloria.

Fragment B begins at “Visibilium omnium” and contains five descending notes. As the sopranos come down, the tenors go up the same five notes in a crossing pattern. This is identical in structure to the phrase noted previously in passing in the Sanctus of “K66”. It was such a good sound, Mozart must have filed it away until he could develop it further.

Fragment C begins with “ET IN UNUM DOMINUM” and consists of five ascending notes, with each group in the chorus chiming in one after another, almost identical to the “Kyrie2” theme above, only major instead of minor. Fragment C is accompanied by the violins furiously doing what sound literally like ascending and descending scales.

Scarcely a line of text goes by without a run of a substantial piece of the scale, though none is a recurring theme: five notes down at “Dei unigenitum“, five down at “Ante omnia saecu-la”, five down (one chromatically) at “Deum de Deo, lumen de lumine“, four up at “DE DEO VER-o”.

- Fragment C returns for “GENITUM NON FACTUM“,

- Five notes go down and five right back up at “Per quam omni-a/, PER QUAM OM-nia“.

- Fragment A returns for “QUI PROPTER NOS HOMINES“.

- Fragment B returns for “Descendit de cael-is, de caelis descend-it“.

- Six notes go down at “Descendit, descendit, descen-dit“.

ET INCARNATUS EST

The first slow section is the soft, hymnlike “Et incarnatus est”, with a gentle antiphonal effect as the sopranos and tenors call and the altos and basses respond. It is brief, but still long enough to have two repetitions of a descending four notes. The slow, loud “Crucifixus” begins with the basses loudly interrupting the reverie of the other singers by intoning seven rising notes, neither major nor minor, but almost entirely chromatic. The tenors pick up the scale with another five, the altos with six, and finally the sopranos finish the run with five more, for a total of twenty-three of the twenty-five notes of two chromatic octaves. A musical snippet here would have to be the full two minutes of the section, so just listen and you’ll hear it easily.

ET RESURREXIT

The second fast section brings back the music of the opening fast section at “Et resurrexit“. A variant of the A fragment is immediately recognizable because of the orchestral music, even though the scale goes down instead of up.

The C fragment is perfectly suited to the words “ET ASCENDIT IN CAELUM“.

Four notes go down at “Sedet, sedet ad dexteram Patris“.

Fragment B is easily recognizable at the single word “Vivos“, even though the chorus sing only two of the four notes, while the orchestra do the rest, similar to the effect in “QUI TOLLIS” in the Gloria. The music comes to a reverential stop for “Et mortuos“.

The music at the words “Cujus regni non erit finis” deserves special mention. The strong (nonsequential) first-four-note motif is identical to the same phrase in “K66” and the effect is strikingly similar to that in “K139”. In addition, all three settings include the playful repetitions of “Non”. Along with God’s kingdom, this theme also, apparently, will have no end. I will designate the two repetitions of “Non, non” as Fragment D, as it will recur.

The scale motif appears here one last time as six notes down at “Non erit, not erit, non e-rit”.

ET IN SPIRITUM SANCTUM

The second slow section invites comparison with the same text in several other Mozart masses. Of his sixteen complete masses, the Credo is the longest movement in thirteen. This is partly due to the length of the prayer itself; partly due to Mozart’s convention of setting off “Et incarnatus est” and “Crucifixus” as a separate section, even in his short masses; but also partly due to his fondness for this particular passage.

The longest Credo is in “K66”, with a length of over fifteen minutes for the mean of conductors Matt, Kegel, and Harnoncourt. The shortest is in “K259” at about three and one-half minutes. The Credo in “K167” is clumped in a virtual tie for second, third, and fourth longest at just over twelve and one-half minutes. One of the others is the intentionally long cantata mass “K139”; the other is “K262”. The next longest Credo is a distant nine minutes in length in “K257”.

A significant part of the lengths of these four movements are the lengths of “Et in Spiritum Sanctum”, which take up about 20% of their Credo movements. Most of Mozart’s settings of these words run about 30 seconds and involve soloists, alone or in combination. Only five are over one minute: the ones in these four longest masses, “K139”, “K66”, “K167”, and “K262”, and in “K49” (a special case of a long setting in a short mass, as discussed in its own chapter). All but “K167” are extended songs for soloists.

Four Longest Credo Timings by Conductor

| Credo Length | Matt | Kegel | Harnoncourt | Mean |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total “K66” Credo | 16:12 Matt | 14:14 Kegel | 14:44 Harnoncourt | Mean 15:03 |

| Total “K139” Credo | 12:45 Matt | 12:44 Kegel | 13:19 Harnoncourt | Mean 12:56 |

| Total “K167” Credo | 12:32 Matt | 12:02 Kegel | 12:59 Harnoncourt | Mean 12:31 |

| Total “K262” Credo | 11:58 Matt | 12:36 Kegel | 10:52 Harnoncourt | Mean 11:49 |

Relationships Between Mass, Credo , and “Et in Spiritum Sanctum” Length (Matt Timing)

| Mass | Credo | “Et in Spiritum” | Rank By Total Time | % Credo | Rank by # of Measures |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| “K139” | 12:45 | (1:51) | 42:56 (2) | 15 | 1005 (2) |

| “K49” | 07:16 | (1:30) | 17:43 (10) | 21 | 471 (11) |

| “K65” | 04:55 | (0:37) | 12:55 (16) | 13 | 348 (16) |

| “K66“ | 16:12 | (3:01) | 46:10 (1) | 19 | 1110 (1) |

| “K140” | 04:47 | (0:28) | 16:17 (13) | 10 | 512 (10) |

| “K167” | 12:32 | (2:46) | 29:03 (4) | 22 | 847 (3) |

| “K192” | 05:42 | (0:25) | 20:53 (8) | 7 | 557 (7) |

| “K194” | 05:34 | (0:34) | 15:36 (14) | 10 | 457 (12) |

| “K262” | 11:58 | (2:40) | 30:00 (3) | 22 | 824 (4) |

| “K220” | 04:26 | (0:21) | 16:23 (12) | 8 | 360 (15) |

| “K258” | 04:47 | (0:27) | 17:32 (11) | 9 | 436 (13) |

| “K259” | 03:39 | (0:23) | 13:19 (15) | 11 | 375 (14) |

| “K257” | 09:00 | (0:55) | 27:46 (5) | 10 | 666 (5) |

| “K275” | 04:53 | (0:25) | 19:10 (9) | 9 | 523 (9) |

| “K317” | 06:55 | (0:40) | 26:43 (6) | 10 | 630 (6) |

| “K337” | 05:49 | (0:35) | 21:47 (7) | 10 | 530 (8) |

| Mean of 11 – Short “Spiritum” | 05:30 | (0:32) | 19:16 | 10 | |

| Mean of 5 – Long “Spiritum” | 12:10 | (2:22) | 33:10 | 19 |

In this mass, after a gentle and courtly orchestral introduction, the chorus jump right in with six notes going down the scale at “Et in Spiritum Sanctum Domin-um“. After an orchestral passage, five notes descend followed by four at “Qui ex Patre Filioque“. Then there’s nothing until the six notes of the initial music repeat at “Qui cum Patre, cum Patre et Fili-o”. And, at the very end, six notes descend at “Est per prophetas“.

Ultimately, this second slow section of the Credo comes off as a long and uninteresting Type I song for chorus and orchestra. The tightness of construction and attention to detail in the rest of the movement leave Mozart looking kind of lazy here. The orchestral part is so much more airy than the plodding vocal part that the chorus are actually in the way. This would be more at home as a purely orchestral movement in a symphony or divertimento. It just does not work here.

ET UNAM SANCTAM

Mozart is back on track for the third fast section, which brings back an extended Fragment A with “Et unam sanctam catholicam“ containing five notes down at “Confiteor unum baptisma in…” before the rising motif, which here is six notes, at “reMISSIONEM PECCAtorum”.

Fragment C returns for “ET EXSPECTO RESURRECTIONEM“.

The action stops dramatically for “Mortuorum“.

ET VITAM VENTURI

And finally, for the fourth fast section, there is an extended Type II chorus on “Et vitam venturi saeculi“. The vigorous new theme has four descending notes. The countertheme is a five-note cascading descending motif that sounds very much like laughter when sung. Is Mozart having the chorus say, “Ha ha ha! Take that, Satan, we have everlasting life!”? Or, “Ha ha ha! Who needs soloists?”? Or, perhaps, “Ha ha ha! Take that, Archbishop!”? Could this extra-long Credo in a non-cantata mass have been the beginning of Mozart’s defiant relationship with the archbishop’s demands for brevity?

At the beginning of the sopranos’ last extended “Amen“, there is another reference to a Kyrie theme—the first phrase the chorus sing, “Kyrie1”.

And just before the close of the movement, during the extended “Amen“, Fragment B makes a final satisfying appearance, followed by the “never-ending” Fragment D and a final gale of laughter.

SANCTUS

“Sanctus” is short and straightforward, a joyful Type I hymn of praise in triple time, squeezing in a couple of descending runs: sopranos have six down at “Dominus Deus Sabaoth”; basses have five down twice at “Glo-o-o-o-o-o-oria tua”.

“Hosanna” is a crisp and joyful chorus, all Type I, with five notes up and four down right out of the gate: “Ho-SANNA IN EXCEL-sis, hosanna in excelsis“.

Remember Tovey’s claim in my chapter on “K66” about “Hosanna” having an intentional stress on the third syllable in an unnamed Mozart mass? I was sure it couldn’t be in “K66”, but this “Hosanna” could be a contender. There are not forty to fifty repetitions of the word, there are no accents or indications for loudness, there is no stretto or syncopation, as Tovey insists. However, having “-na“ fall on the strong first beat of each measure in the second phrase accents it naturally by the singers, and it is punctuated by loud beats from the timpani.

In the absence of any other “teasing” elements, such as are present in “K66”, I don’t find a strong case for Tovey’s argument here, either. We’ll visit him again in “K262” and “K257“.

BENEDICTUS

I think this is one of the few movements where conductor Nicol Matt gets it wrong. All of Mozart’s preceding settings of “Benedictus qui venit” have been gentle, flowing, songlike movements consistent with the “blessed” words. Herbert Kegel and Nikolaus Harnoncourt both let the music “breathe” and unwind at a measured pace, while Matt races through it. Listen to the difference: Kegel Introduction; Matt Introduction. My snippets for this movement are from Kegel.

The orchestra is an equal partner in this movement, weaving a countermelody which never interferes with the chorus. This interplay works so much better than in the “Et in Spiritum Sanctum” section of the Credo. The long orchestral introduction makes us feel we are home free with regard to the scale motif, with easily identifiable runs up and down. The chorus, however, are more sparing in their use. As in the “Qui tollis” text of the Gloria and the “Vivos” phrase in the Credo, the chorus several times share a run with the violins, singing only one or two notes of the scale:

“XXX BE-NE-dictus XXXX QUI venit”

But they also have their own complete four- and five-note runs:

“in no-o-o-o-…-o-o-mi-ne do-…-o-mine” and “in no-o-o-o-O-O-O-O-o-o-mi-ne do-mine“.

There is a second verse using the main theme with similar repetitions of the scale runs.

Between the two is a musical interlude that again deserves two examples. Matt lets the cadence fall on its face with a splat; Kegel lets the oboe soar and the cadence take a courtly bow.

The chorus’s minimalist dialogue with the violins repeats twice more, and finally, there are descending runs of five and six, the second leading directly into “Hosanna”.

“Hosanna” follows as usual.

AGNUS DEI

“Agnus Dei” is a Type I chorus. This is sung as a hymn with the phrases interspersed with independent orchestral music. The integration is so complete here that the chorus basically take over the orchestra’s music by the end of the section. The words repeat several times, beginning softly and rising to a final impassioned cry.

The orchestra begin a lilting introduction with runs up and down the scale, punctuated by a fanfare in trumpets and timpani. The chorus enter with the hymn at “Agnus Dei”—lovely, but not as much fun as the orchestra’s little riff. The chorus dutifully fulfill the scale “requirement”, going down at “miserere nobis” and up again at the next “AGNUS DEI QUI TOLLIS PECCA-ta.”

Apparently envious of the orchestra’s music, they then horn in on it by doubling one of the orchestra’s scale runs for the next “Agnus de-i“. In addition, the tenors and basses join the fanfare.

The last time through the words, the chorus dispense with any attempt at the hymn tune, and all four voices just sing the fanfare part in unison.

DONA NOBIS PACEM

“Dona nobis pacem” is a spirited Type II chorus. The first four notes of each voice are strongly accented, as in the “Cum sancto spiritu” text of the Gloria, but here, instead of being the same note, they are widely spaced and about as far from a scale run as is possible. And, as in “Cum sancto spiritu”, the countermelody supplies the runs, beginning with the tenors and followed by the sopranos. The altos and basses each get their licks in as well, but none of these is musically prominent. Finally, near the end, the sopranos leave no doubt that the scale motif is a strong part of every movement of the mass.

–02/01/2011-5/02/2011

![]()