MASS IN C MAJOR, K66

INTRODUCTION

Mozart wrote this cantata mass in honor of the first solemn mass celebrated by the newly minted priest Pater Domenicus on 15 October, 1769, at St Peter, the abbey church of the Benedictine monastery in Salzburg. This was Cajetan Hagenauer, ten years Wolfgang’s senior and one of eleven children of the Mozarts’ landlord.

I have seen nothing in biographies about Wolfgang in childhood playing with age peers, though sometimes he would run around madly by himself with a stick horse between his legs. Mostly, he was surrounded by adults involved in his musical development. The trumpeter Schachtner would play with him, but whenever they went from room to room, one would carry the toys and the other would have to sing or fiddle a march. At Leopold’s instigation, Schachtner would sneak up on the boy and blare a note on the trumpet, which would cause Wolfgang nearly to faint. Leopold apparently found this amusing.

The only hint I could find of his relationship with Cajetan was that when Wolfgang learned in London in 1766 at the age of ten that Cajetan was entering the priesthood, he wept and feared he would never again be able to catch bugs and shoot air guns with his “best friend”.

The Mozart family and their friends were highly involved in this domestic recreation (not the bug-catching), called Bözlschiessen, which involved shooting darts with an air gun at painted targets containing pictures and verse satirizing or embarrassing some member of the party. For example, one target depicted one of Wolfgang’s sister’s friends tripping on a step and exposing her buttocks. There were cash prizes and part of the hilarity must have involved where one’s dart came to rest.

I would not be surprised if there are personal references or private jokes with Cajetan in this mass. If so, we shall just have to guess what they are. I am happy to go first.

One possibility is suggested by the prevalence of triple time, which appears in 9 of 20 rhythmic sections (45%) as opposed to 7 of 23 such (30%) in “K139”. European dancing prior to 1750 had been a chaste hands-off arrangement between the sexes, and triple time meant the courtly minuet. The nefarious influx of triple-time “whirling dances” derived from the hobnail-boot-stomping Ländler, in which couples actually put their hands on and arms around each other, was being observed among the common folk in southern Germany to an alarming degree. Indeed, in 1752, Salzburg’s Prince-Archbishop Andreas Diedrichstein banned all such dances, probably cementing their eventual name as walzes (walzen = “to roll, turn”). Nobody much paid attention from a legal perspective, as these dances were increasingly popular among the children of even decent people, but the older generation continued to view them as immoral.

Perhaps Cajetan enjoyed defiantly stepping out to dance halls in his teens and regaled the young Mozart with what it was like to touch girls. In 1769, at thirteen, Mozart would be starting to understand. The walzes in this mass could be teases to Cajetan that, as a priest, he must now renounce such things.

In addition, there are a couple of instances where voices enter in the “wrong” place. There are also several places where voices sing in the “wrong” rhythm. And there are a couple of words of text where the stress is intentionally on the “wrong” syllables. Perhaps Cajetan had difficulty with timing and pronunciation in church or when he and Wolfgang sang together, as I imagine they must have done while catching bugs.

The mass is scored for 2 oboes, 2 horns, 4 trumpets, timpani, violins, violas, basses, organ continuo, and 3 trombones doubling alto, tenor, and bass vocal parts. The oboes are replaced by flutes for the “Gloria in excelsis”, “Laudamus te”, and “Gratias agimus” sections of Gloria and for the “Et in spiritum sanctum” section of Credo. I can’t hear a specific contribution by the flutes in “Gloria in excelsis” or “Gratias agimus”, but they are absolutely essential for “Laudamus te” and “Et in spiritum sanctum”. Oboes would sound simply awful in those two sections.

KYRIE

The Kyrie begins as a Type I chorus in duple time. The slow, measured tones and modal chord changes provide a churchy-sounding Introduction in duple time.

The music quickly turns to triple time and the chorus skip their way gaily through the rest of the movement. Mozart gets a lot of mileage out of three repeated brief theme fragments plus a concluding fragment, partly because the repeats of Theme A and Theme B sound quite different in the minor mode the second time through and partly because reverting to the “Kyrie” words for Theme B’ suggests to the ear that this is a new section instead of another “hybrid” like the Kyries of “K139”, “K49”, and Leopold’s “Missa Solemnis”. Theme C suddenly appears twice and sounds particularly danceable.

- Theme A—“Kyrie” (chorus)

- Theme B—“Kyrie” (chorus)

- Theme C—“Kyrie” (soloists)

- Theme A’—“Christe” (chorus)

- Theme B’—“Kyrie” (chorus)

- Theme C—“Christe” (soloists)

- Theme D—“Kyrie” (chorus)

There is little wasted thematic material, as the Introduction, Themes A, B, C, and D all share a falling four-note phrase (Introduction4, Theme A4, Theme B4, Theme C4, Theme D4).

GLORIA

GLORIA IN EXCELSIS

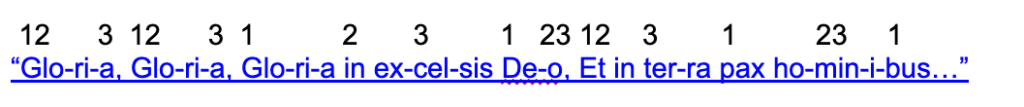

The Gloria begins with a rafter-raising Type I chorus in triple time. Mozart wastes no time in having the rhythm step on its own feet:

sounds like

The “gotcha” could be intended for Cajetan’s ears if he liked to hum along or could just be Mozart being playful. By the time our ears get back on track, especially after additional syncopation, the brief section is over.

LAUDAMUS TE

“Laudamus te” is an ingenuous song for soprano and alto. It may not be a waltz, but it’s at least a slow dance (if they did that sort of thing in the eighteenth century). The soloists sing alternately (soprano, alto) rather than together, presenting the range of notes and timbres as if a single voice. Their phrases get closer together, and the presence of flutes is reminiscent of the sound of “Benedictus” in Leopold’s “Missa Solemnis”. Finally they sing together at the end.

GRATIAS AGIMUS

A brief, straightforward “Gratias Agimus“, a Type I chorus in duple time, does not stray far from the chord on which it starts. It has a majestic sound.

DOMINE DEUS

“Domine Deus” returns to triple time and is a song for tenor. The tune is lovely, but I would submit not ingenuous, no matter how gently the singer might try. The sound of the string of notes that make up the tune is distant, operatic, not folklike.

I made a comparison across all four recordings of the complete masses of this solo with the ingenuous tenor songs in “K139” for “Domine Deus” (duet with bass) and “Et in Spiritum Sanctum” (solo). Matt, Kegel, and Harnoncourt use a different tenor for both masses and Neumann uses the same one. In each set, the two pieces from “K139” sound sweet and intimate, and in each set, this “Domine Deus” sounds pompous and important, as if the singer is giving us a lecture. It’s not the singer: Mozart’s music here simply has too much Hasse and not enough Heinichen.

QUI TOLLIS

The mood turns somber as the chorus intone a Type I “Qui Tollis” in slow duple time. Everything is “by the book” for this emotional heart of the Gloria, except for two things. The first “Miserere” has a notation to play the first and third syllables softly and the second and fourth loudly: “mi-SE-re-RE“. Later, “Suscipe deprecationem” suffers a similar mistreatment: “susci-PE, de-pre-CA-TI-o-nem nos-tram“. What’s that about? Could Cajetan have had a quirk when saying these words when the families attended Mass?

QUONIAM

But just as quickly, the music springs up again in triple time for “Quoniam“, a sprightly ingenuous song for soprano. As in the “K139” “Quoniam”, the presence of melismas does not make this “operatic”; for me it suggests a physical “twirling” as the soprano sings a gentle, open folk song.

CUM SANCTO SPIRITU

A vigorous Type II chorus on “Cum sancto spiritu” in duple time concludes the Gloria. The orchestra are working as hard as the chorus, doubling their lines for the most part for extra emphasis. As the “Amens” draw out in longer duration, the orchestra spy their chance and finally break free with their own independent flourish before the final cadence.

CREDO

PATREM OMNIPOTENTEM

Here’s a mass in which some ecclesiastical rule permitted the musical setting of the words “Gloria in excelsis Deo” but not “Credo in unum Deum”. Go figure. Credo picks up in duple time in joyous fashion where Gloria left off, with the chorus beginning at “Patrem omnipotentem” in Type I fashion and the orchestra, free from voice doubling, playing at a frenzied pace. Mozart organizes the subsections beginning “Et in unum Dominum”, “Et ex Patre natum”, “Genitum, non factum”, and “Qui propter nos homines” with theme changes, separated by very brief orchestral figures. The pitch descends with the words “Descendit de caelis” and the section ends on a grand cadence.

ET INCARNATUS EST

Triple time returns for “Et incarnatus est”, but this gentle waltz is neither light nor playful. The four soloists sing the words together and the mood is serious.

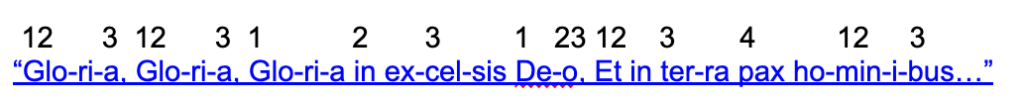

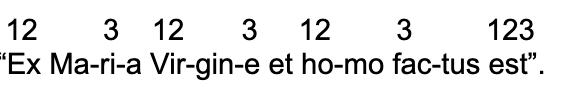

The simple tune itself and phrase length are constantly changing, but there is enough underlying consistency in the sound that the effect is that the song is composed of two identical verses, each with two repetitions of the text, inviting the unsuspecting listener to hum along as in “Gloria in excelsis”.

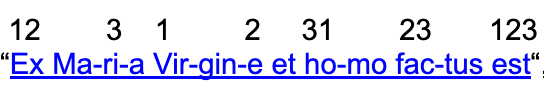

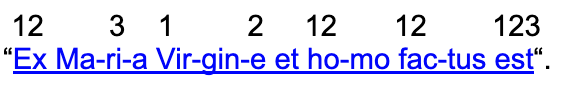

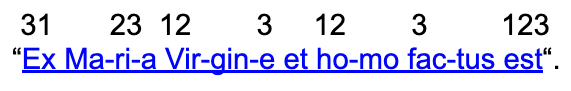

In addition, Mozart slips in a droll syncopation, which is so subtle it does not break the reverent mood. You or I or any other composer would set the next phrase so that the rhythm would be:

Mozart, however, does it like this:

12 3 1 2 31 23 123

as if it has slipped into duple time:

Just as we’re getting used to this quirk, he plays it almost straight one time only at the beginning of the second verse (compare to “you or I” above):

Finally, there are two instances of voices entering at the “wrong” time. In the first line of the first verse, “Et incarnatus est de spiritu sancto“, the soprano sings the “-ri-” in “spiritu” just before the other soloists. One of them, I’m guessing the tenor, must jab her in the ribs, because the other three times the phrase appears, they all sing together at the “proper” time. Then, in the first line of the second verse, right after the soprano comes in at the “right” time, she jabs the tenor back and he yelps a note that doesn’t belong on the “-o“ in “de spiritu sancto“. Everyone recovers nicely without laughing. The lovely song ends as though nothing had happened amiss and all are friends.

CRUCIFIXUS

For “Crucifixus” the chorus return with Type I harmony in duple time. The music is stern and angry.

ET RESURREXIT

The chorus turn jubilant with the Type I “Et resurrexit” in duple time. The music ascends at the words “Ascendit in caelis” and slows respectfully for “Vivos et mortuos“. The setting of “Cujus regni” is very similar to that in “K139,” including the playful repetition of the word “Non“.

ET IN SPIRITUM SANCTUM

“Et in spiritum sanctum” is an ingenuous song in triple time for soprano, again, as in “Laudamus te”, with indispensable flutes. The music is gentle and pastoral in sound.

ET UNAM SANCTAM CATHOLICAM

A brief Type I choral passage in duple time beginning with “Et unam sanctam catholicam” acts mainly as a bridge to “Et vitam venturi saeculi.” It ends on a long, drawn-out treatment of the word “mortuorum“, almost twice the length of the sound sample here, followed by a dramatic pause.

ET VITAM VENTURI SAECULI

The Type II chorus on “Et vitam venturi saeculi” is another waltz, which somehow manages to be both churchy and playful at the same time. Mozart needs no rhythmic teases here, as just the very regular entries of the voices make the rigid formal structure sound quite danceable.

SANCTUS

“Sanctus” is a Type I chorus. The first couple of lines are slow and majestic, like an introduction, in duple time.

The tempo picks up at the line “Pleni sunt caeli” and the meter breaks again into triple time. I note in passing a phrase in this section in which the sopranos and tenors move in opposite directions on the same five notes, followed by the altos and basses doing the same thing. It has no particular significance here (other than that it is most pleasant), but we will encounter this same phrase as one of the rising and falling four or five note fragments unifying Gloria and Credo of “K167” four years later. Stay tuned.

Everything is going fine until the last time through “Gloria tua“, where everybody seems to lose their way, each group coming in in a different place in the same three beats. They quickly get back together, then switch to duple time for “Hosanna”, with brief appearances by the solo soprano and alto. Then at the end, the sopranos, altos, and tenors sing the same short phrase six times in imitation, but the basses go off by themselves, singing “Hosanna” three times

In Donald Francis Tovey’s book of essays analyzing concertos, of all places, he talks of Mozart’s musical “practical jokes” and games and says, “I, for my part, feel absolutely certain of his intention of getting the choir to mock the pronunciation of some friend of his in a certain Mass, once well known, where the word ‘Osanna’ is set in close stretto to a syncopated rhythm, and a fortissimo mark is placed under the third syllable in all the voice and instruments at every single one of the forty or fifty repetitions of the word.”

I like Tovey because he’s smart and arrogant and doesn’t document things any better than I do, but if he’s talking about this mass (which of course I hope he is), I don’t know what he’s been smoking. “K66” is one of only three Mozart masses (the others are “K262” and “K257“) containing between forty and fifty repetitions of “Hosanna”. There is a brief period of stretto (close echo-like imitation) in the last example above, and I guess you could call the rhythm syncopated, but the music clearly puts the stress on the second syllable (or equally on all three), and I assure you, there is not a single fortissimo mark in the score in any voice or instrumental part. I would think the editors of the definitive Neue Mozart Ausgabe might have noticed something like that in the manuscript and made a comment.

Could Tovey have misread his unnamed gossipy source and mean instead the hijinks in the “Qui tollis” section of this mass? There the indications to play loud are in all the vocal and orchestral parts (except the oboe)—but forte (loud), not fortissimo (really loud).

We’ll look at this again in “K167” (which has a third-syllable candidate) and in “K262” and “K257” because of their numbers of “Hosannas”.

BENEDICTUS

“Benedictus”, in duple time, is for soloists. The sophisticated four-part ensemble writing provides an elegant blending of voices and allows each soloist to show off just a little bit without favoring one over the others. The return of the chorus with “Hosanna” provides a satisfying close to the movement.

AGNUS DEI

“Agnus Dei” is a jolly march in duple time for Type I chorus with brief appearances by the solo soprano and alto. The orchestral introduction and interludes establish an infectious foot-tapping rhythm which does not flag even when the chorus sing softly.

DONA NOBIS PACEM

“Dona nobis pacem” begins without a pause with an alto solo. The momentum of the jolly march causes her entry to sound strongly like a return of the duple-time “Hosanna”, as it utilizes the same distinctive note pattern. The chorus burst in as if to say, “No! Gotcha again, it’s one more waltz!” followed by a soprano solo. The tenor and even the bass get solos. They all then proceed to the festive conclusion of the mass without missing another beat—or voice entry.

![]()